Some of the loudest voices in America talk of their support for the second amendment of the U.S. Constitution. But can they actually quote that second amendment? As supportive of it as they claim to be, they don’t know what it says. Hint – it does not say “the people have the right to bear arms”.

Here’s what it actually says:

“A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

Written documents, especially ones written when people used the English language quite differently than we do now, can lend themselves to more than one interpretation.

So let’s then consider the time and culture of the framers of the U.S. constitution. The era is well documented, and the historical facts are much more interesting than the blather being disseminated currently by special interests and their puppets in the media.

Since history is so poorly taught in this country, there’s a tendency to confuse the U.S. Declaration of Independence with the U.S. Constitution. The early years of our country’s independence are also confused with our previous state of being the American Colonies of Britain.

In 1776, the first Continental Congress wrote the Declaration of Independence and all members signed it over a period of a few months. They traveled on horseback from all parts of the colonies to do so and were actually not all together for a single signing event like that depicted in the famous painting. Each signatory was subjecting himself to punishment by death for treason against the King of Britain. No second amendment here.

At the time of the Declaration’s signing, the American Revolutionary War had been in full swing for a year already. This war emphasized the need for a “well regulated militia”, the language used in the second amendment that would not be written for nearly fifteen years yet.

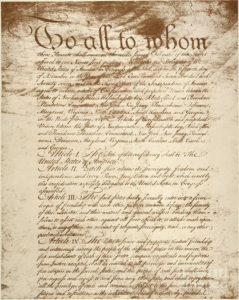

But for now as a document to agree on how our newly unified colonies would operate, the second Continental Congress wrote the Articles of Confederation, which were ratified by each state in late 1777. A pre-constitution constitution, so to speak.

Contained within the Articles of Confederation is this quote:

“every state shall always keep up a well regulated and disciplined militia, sufficiently armed and accoutered, and shall provide and constantly have ready for use, in public stores, a due number of field pieces and tents, and a proper quantity of arms, ammunition and camp equipage.”

The 1776 Virginia Constitution includes Article 13 of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, and it says:

“That a well-regulated Militia, composed of the body of the people, trained to arms, is the proper, natural and safe defense of a free State; that Standing Armies, in time of peace, should be avoided as dangerous to liberty; and that, in all cases, the military should be under strict subordination to and governed by the civil power.”

This shows a militia was preferred to a standing army, which most of our country’s founders thought to be too expensive and potentially even dangerous. The British professional army had been occupying much of America for years, and most colonists saw them as drunkards and abusive to citizens.

It’s important to remember that in 1776 we were still under British rule; we had only just made a “declaration” that we wanted to be independent. We would not become an actual sovereign nation until nearly fifteen years later, after we’d won the Revolutionary War and adopted our own constitution — one that all the states could agree upon.

For the previous century the colonists had established their own well-regulated and disciplined militias in order to defend themselves. The Articles of Confederation stated that this would remain the plan for our rogue but newly united colonies.

The Articles indicate that the arms would be in public stores and includes things other than guns. This was to ensure that the equipment was kept up and “constantly…ready for use”. That included the guns. The guns would all be of the same type so that parts and ammunition would be interchangeable, as opposed to each militiaman bringing his own gun and ammo. Individuals keeping a gun at home did not insure proper maintenance or availability. So weapons were kept in a public storage place where someone was given the task of ensuring their readiness.

Also, the men using these guns were to be “well-regulated and disciplined”, the only real way to effectively fight together. They would know where to go and what to do when needed, like on the night Paul Revere (and others) rode out proclaiming that “the British were coming”.

That night the British were marching toward what they thought was the Massachusetts Militia’s arms storage house. But it wasn’t a bunch of guys being awakened by Paul Revere and then each grabbing his own gun and fighting against the most powerful army in the world. It was the well-regulated and disciplined Massachusetts Militia. They didn’t have uniforms, but they were trained and registered to use the equipment, or “arms”, including but not exclusively meaning guns.

Another thing to consider is the phrasing and general use of the English language at that time. The Oxford English Dictionary defines “to bear arms” as meaning, “to serve as a soldier, do military service, fight.” The Virginia Constitution and other state constitutions written at the time uses the term “trained to arms”. This was known to mean trained to defend, offend, or fight in an organized fashion, like military fighting, or militia fighting.

July 12, 1780 – Trained Patriot Militia wins first southern victory against British Army in S. Carolina using regulated arms

So the colonists declared themselves independent from Britain in 1776 and ratified a general agreement between what they began calling the states. But the British still considered them their colonies in 1777. For the colonists it was an ongoing revolt, with this revolutionary war being waged for many more years. There was still a long way to go before the creation of our “United States” and a United States Constitution.

In 1783, Britain finally surrendered, and we began to be recognized around the world as our own sovereign nation. Now the fight began amongst ourselves to determine what kind of nation we wanted to be. Up to now we had been functioning as self-governing colonies. How would we work together? A revision of the Articles of Confederation would need to happen to create a national constitution.

Delegates for the states were chosen to attend what’s now known as the “Constitutional Convention” in Philadelphia from May to September of 1787, but not all of the states participated. A quorum was eventually achieved, meaning just enough states were represented to have authority to debate, and on September 17th the arguments over the establishment of a federal government ended and the delegates signed off on the constitution. But actual acceptance by all of the states would be another years-long fight.

Almost immediately opposition to the constitution began, with the first “anti-federalist” argument being published on September 27th. Nine states need to ratify the constitution in order for there to be a majority agreement on how our federal government is to be structured.

James Madison, the main author of the constitution, goes around to each of the states’ “ratification conventions” trying to get each of them to sign off on the document. One of the most important states was Virginia, which had a population of more than 40% slaves. Talk in the north against slavery had begun and Virginia, being on the north’s southern border, was in constant fear of a slave insurrection. Their only defense was their militia.

The constitution included the “Militia Clause” that said, “The Congress shall have Power To …provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions….” ARTICLE I, SECTION 8, CLAUSE 15.

Virginia feared the new federal government could ask the Virginia militia to go elsewhere to defend against an uprising and leave the state vulnerable to a slave insurrection. Other states had this fear as well. In response to their concerns and to hasten the constitution’s ratification, Madison agreed, with the coercion of fellow Virginians, Thomas Jefferson and George Washington that a “bill of rights” could be discussed later in congress in the form of amendments to the document.

Two years later, after we set up our first congress and elected our first president, twelve articles of amendment were presented in the congress on Sept. 25th 1789. Articles Three through Twelve were officially ratified as amendments to the constitution on Dec. 15, 1791. These ten amendments are the Bill of Rights, the second of which is my focus here. (Interesting to note: Article Two wasn’t ratified until 1992, and Article One is still pending before the states.)

An important factor in the addition of the second amendment was the Shays’ Rebellion of 1786. Lead by former Continental Army captain Daniel Shays, Western Massachusetts’ farmers revolted against the new government for not addressing their financial grievances. Wealthy Bostonians had to fund their own militia to bring an end to the rebellion in February of 1787.

A weak federal government as drafted into the Articles of Confederation could not fight against such uprisings without the already established state militias, and President George Washington realized this. A successful uprising so early in our existence would only prove Britain’s prediction that our independent colonies would soon descend into chaos. So, although he felt we should have a standing professional military, Washington knew we would need to maintain our state militias to quickly deal with uprisings among our own citizenry. That meant that maintaining the state militias would need to be added to the constitution.

So the wording of the second amendment helped appease southern states that wanted to be guaranteed they wouldn’t have to give up their state militias, and it also established a tried and true defense against domestic threats. It also allowed us to keep only a bare-minimum standing military.

It’s important to note that the second amendment neither prohibited nor protected the right of an individual to own and/or carry a gun.

Later acts of Congress and Supreme Court rulings would use the wording of the second amendment to uphold gun regulations. During WWI, General John T. Thompson wanted to develop a hand-held machine gun to help the U.S. forces. He came up with a working version, but the war ended two days before he was going to send a shipment of them to Europe. Since the military no longer needed it, General Thompson’s new company decided to try and make their money back by marketing the gun to the public. They named it the “Thompson Submachine Gun”, later to be known as the “Tommy Gun”.

The Tommy Gun played a major role in the mob violence of the twenties and thirties. Using military grade weapons, the criminals were better armed than the authorities. So in 1934 Congress passed The National Firearms Act (NFA) which ruled military grade weapons, along with some other guns and silencers, had to be registered and taxed.

In a 1939 challenge (United States vs. Miller) to the NFA, the Supreme Court used the language from the second amendment to uphold the NFA in this quote,

“The Court cannot take judicial notice that a shotgun having a barrel less than 18 inches long has today any reasonable relation to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia, and therefore cannot say that the Second Amendment guarantees to the citizen the right to keep and bear such a weapon.”

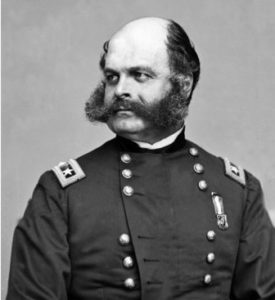

By this time there was an organization thought to be an authority on the safe use of guns. Established in 1871, this new organization was inspired by a Union Army report that said there were about 1000 rifle shots by Union Soldiers for each Confederate soldier hit. This organization’s first president was General Ambrose Burnside (after whom sideburns are named), and the eighth president of this organization was General and later President Ulysses S. Grant. The primary goal of this organization was to “promote and encourage rifle shooting on a scientific basis.”

Congress gathered representatives from this organization, along with members of the National Guard and the United States military, to create the National Board for the Promotion of Rifle Practice in 1901.

You guessed it — the organization I’m describing is the National Rifle Association or the NRA, and it supported both The National Firearms Act in 1934 and the Gun Control Act of 1968.

It wasn’t for more than one-hundred years into the NRA’s existence that it turned into the entity we know today. In 1995 President George Herbert Walker Bush resigned his lifelong NRA membership. His resignation letter included this paragraph describing part of a membership drive letter the NRA had sent out, “I was outraged when, even in the wake of the Oklahoma City tragedy, Mr. Wayne LaPierre, executive vice president of N.R.A., defended his attack on federal agents as “jack-booted thugs.” To attack Secret Service agents or A.T.F. people or any government law enforcement people as “wearing Nazi bucket helmets and black storm trooper uniforms” wanting to “attack law abiding citizens” is a vicious slander on good people.”

After seeing firsthand what President G.H. Bush thinks, one can speculate as to how General Burnside or President Grant would feel about the current state of their NRA.

I write this with hope that more people will be like you and actually inform themselves on the real history of our great country.